Five Things: ICE, Cancer in Iowa, Universal Basic Capital, Curveball, Conspiracy Theory

It's Sunday. Read this now.

Hello and welcome back to Five Things!

Yesterday morning I took our oldest daughter to the train station to get her on a train to Brussels, where she’ll be an intern at the EU Parliament for the next three months. While I am so happy for her to do this next step after getting her bachelor’s degree a few weeks ago, I also already terribly miss her. That’s one of the wonders of parenting: after some time you want your kids gone and start their lives on their own while you simultaneously want them to stay around for ever. Of course, I am trying to come up with ideas for traveling to Brussels without looking like a parent who can’t let go of his kid…

Here are this Sunday’s Five Things - enjoy!

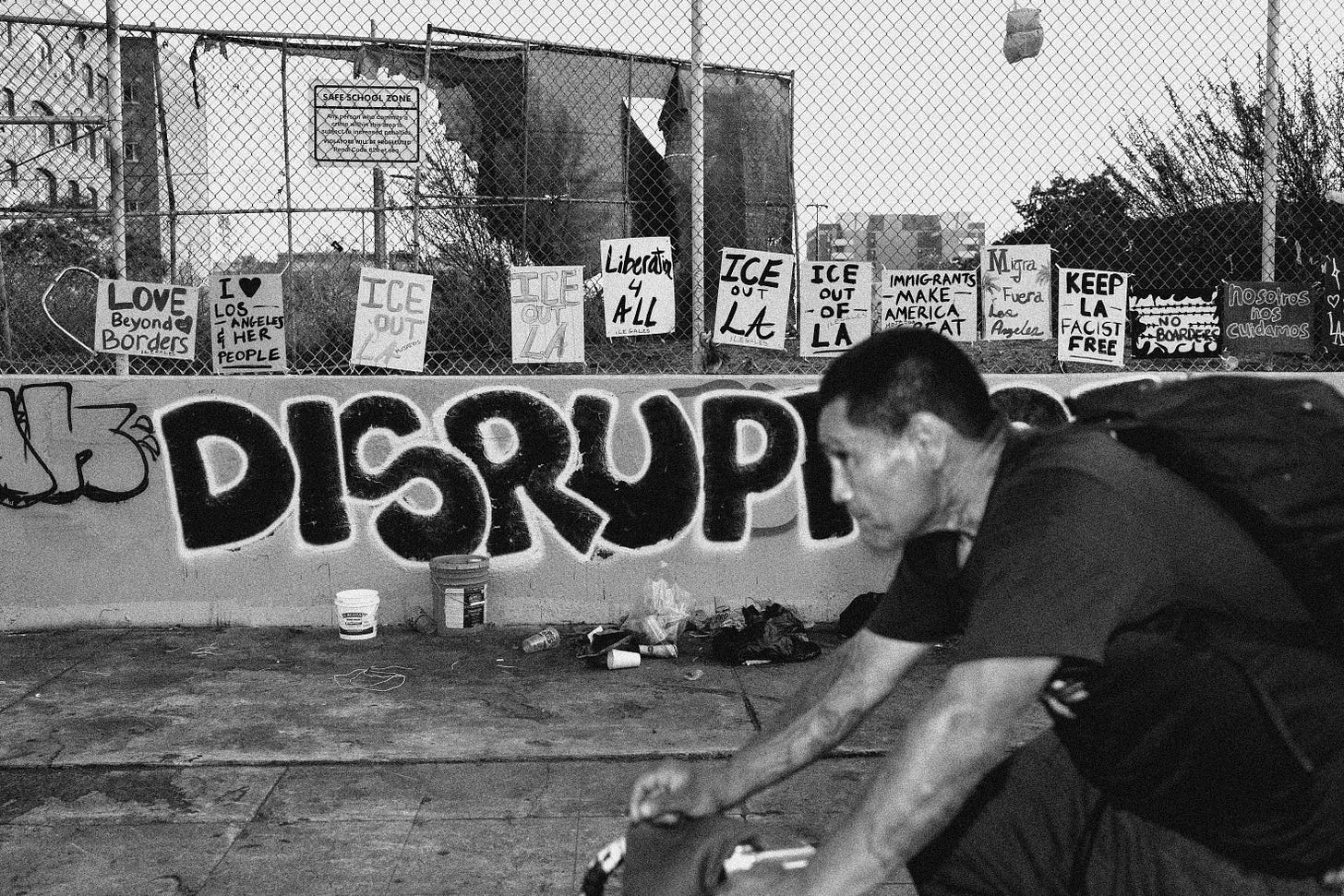

ICE Watch

The one place with enough federal land to facilitate a federal occupation in Los Angeles is Terminal Island. It has just one road in and out, where all the masked and unidentified agents have to go to clock in, and where all the unmarked cars depart from, headed all over the state of California, as far south as the border, as far north as Ventura County. And because there is no one to keep ICE accountable—not the courts, not the Los Angeles Police Department, not a politician or elected official who will force these agents to doff their masks, to show their badge numbers, to identify themselves, to use warrants, to comply with judicial rulings, to obey with traffic laws—well, what was left was this group of nurses and teachers, who, for all summer and now the early days of fall, had been compiling intel. They had plate numbers and makes and models of cars, and sometimes even VINs; they had scouts and lookouts; they had canvassed businesses and compiled surveillance footage. They were keeping a record. They were divining patterns and proclivities. Anyone could be ICE—but so could anyone tip off a vulnerable person before the agents showed.

ICE is right of the Hermann Göring playbook for destroying democracy.

Of Corn and Cancer: Iowa’s Deadly Water Crisis

Today, Iowa has the nation’s second-highest cancer rate—behind only cigarette-heavy Kentucky—and also its fastest-growing. Breast, prostate, and kidney cancers made up three of the top eight new cases recorded this year, according to the 2025 Iowa Cancer Registry. Like everyone in the modern world, Iowans live amid known cancer triggers that have nothing to do with proximity to industrial farming: alcohol consumption, exposure to microplastics and industrial chemicals, and poor sleep patterns. “But if you look from 50,000 feet at what’s going on in Iowa, two things stand out that really distinguish us as very much outliers from surrounding states,” said Richard Deming, director of the Cancer Center at MercyOne Hospital in Des Moines.

As an Iowan by heart this hits hard.

Universal basic capital would create a fair AI economy

Some in Silicon Valley have embraced the concept of universal basic income. But this is essentially a redistributive transfer that would not move the needle on inequality. The alternative concept is universal basic capital (UBC). This is a better fit for the digital economy of the future. It invites all those who labour for their living to earn value from investment in the technology. In short, it is predistribution, not redistribution. The primary instrument for achieving this would be universal investment funds. All citizens would participate through individual or family accounts that hold shares across the AI economy.

We have to seriously debate how we want to create more just societies again and income distribution is a huge part of it.

When Baseball Threw Physics a Curve

A century of debate about the curve shows how professional and amateur sports served as venues not only for entertainment but for knowledge production. Curving baseballs invited researchers to rethink their understanding of physics and test inherited theories against physical demonstration. In turn, the debates brought new understandings of physics to a reading and sporting public. Debating the curve was an opportunity to grapple with the complexity of our physical world. But the curve controversies were also about what it meant to live in that world, and particularly what it meant to be American; about truth and deception in public life. The very question of whether there is such a thing as a curveball revealed how our societies and our knowledge of the physical world evolve in constant dialogue.

Ah, baseball science. What a wonderful sport as it allows for so much interesting discussion.

It’s never been easier to be a conspiracy theorist

In every systemic or superconspiracy theory, the world is corrupt and unjust and getting worse. An elite cabal of improbably powerful individuals, motivated by pure malignancy, is responsible for most of humanity’s misfortunes. Only through the revelation of hidden knowledge and the cracking of codes by a righteous minority can the malefactors be unmasked and defeated. The morality is as simplistic as the narrative is complex: It is a battle between good and evil.

Notice anything? This is not the language of democratic politics but that of myth and of religion. In fact, it is the fundamental message of the Book of Revelation. Conspiracist thinking can be seen as an offshoot, often but not always secularized, of apocalyptic Christianity, with its alluring web of prophecies, signs, and secrets and its promise of violent resolution.

Conspiracy theory really amazes me. We have so much information and such easy access to facts, yet still people opt for completely bizarre explanations that can be debunked within seconds, but they choose to belief them.

That’s it. Have a great Sunday! If you missed last Sunday’s edition of Five Things, have a look here:

— Nico